There’s something that happens when you disguise yourself in the costume and huge head of a sports mascot. You can try absolutely everything…become anything you want…do anything you want to do. Which is perhaps why Amanda Nanasy was the ideal choice to become Knightro, the beloved mascot of the University of Central Florida (UCF) and to become, well…whatever she wanted to be.

So many choices

When a young Amanda Woodie roamed the classrooms and fields and gyms and pastures and horse barns of Auburndale, Florida, she was what parents used to encourage their kids to be. Today, kids are encouraged to do only one thing from an early age, choose between baseball and lacrosse. Are you going to swim or play basketball? Decide so you can get that scholarship and move into your carefully curated life.

But that line of thinking would have been impossible with Amanda. There was too much to do. Too much to explore. Too much fun to be had moving from one thing to another. The daughter of a police officer mother and musician father, Amanda was a cheerleader, an outstanding student, a member of the school band…and hopelessly devoted to her horse.

“Every day after school, I would do my homework in the stall with my horse. When I think of my childhood, I think about laying in a wheelbarrow reading a book with my horse just hanging out near me.” And her horse would go on to play an important role in Amanda’s future…when she fell off and broke her arm. In an instant, her cheering career ended, and her dance career began. And in hindsight, that broken arm helped her decide her future.

All about focus

It might not be surprising that the girl who wanted to do everything didn’t really know what she wanted to do.

The major decision about where to attend college was relatively easy. With her parents’ divorce in her senior year of high school, Amanda wanted to be close to her mother and immediately fell in love with the UCF campus.

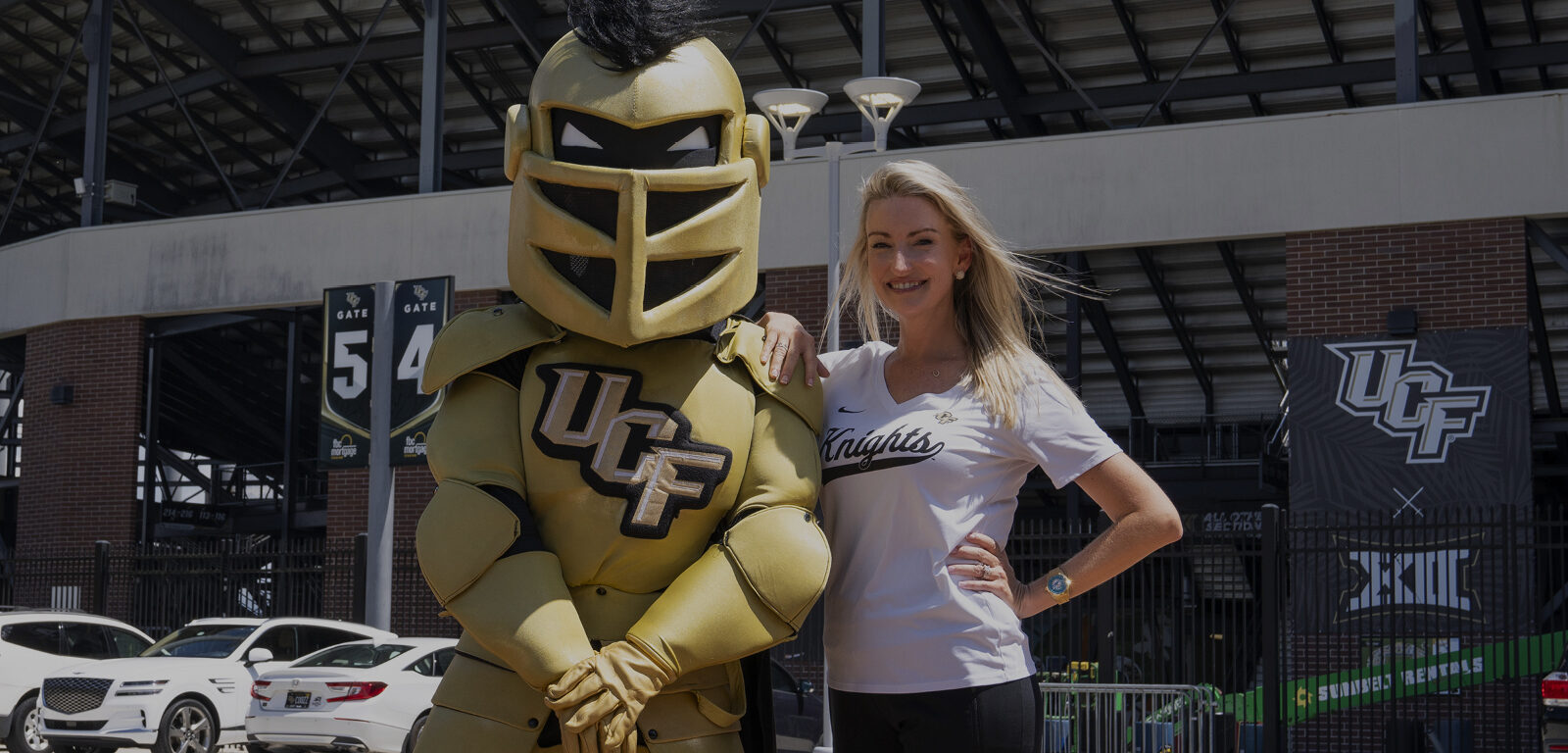

At UCF, her manic lifestyle continued. She joined a sorority. She was an RA, which paid for her dorm room. She was a tour guide, which brought a scholarship. She waited tables. Volunteered at a hospital. And she auditioned to be Knightro, the popular mascot of UCF athletics. But beyond knowing that she wanted to stay busy, help pay for school, and become a doctor of some sort, the future was the future…and there was time for it to work itself out.

Oncology and neurology seemed like obvious choices given the circumstances of her childhood. When Amanda was young, her brother Greg battled a brain tumor—a battle he eventually lost. “I always knew I wanted to be a doctor from the time I was really little, because as a kid when Greg was sick, I didn't understand why no one could fix him. So, I was like, I want to be someone that can fix this type of situation.” But ultimately, she realized she simply couldn’t be surrounded by such tragic situations and such profound loss on a daily basis. “I was, I think, wise enough to know that I wear my heart on my sleeve, and I just wouldn't be able to take that home every day.”

Similarly, Amanda loved animals, but didn’t want to hurt them, even in an effort to heal them.

She was physically active and had an interest in sports medicine, especially after being treated for her broken arm. But after shadowing several orthopedists, she realized the lifestyle of being on call might not be for her. But her visit was eye-opening in one important way. “I walked in, and the doctor had all kinds of sports jerseys on the wall and I thought that it was such a cool concept to be able to help get those people back to doing what they love. So that's when I thought maybe I wanted to work with athletes; coming from barrel racing and sports, it was part of my DNA.” But with doubts about a future in orthopedics, she would take another year to decide on a future path.

That path became clear when she visited her optometrist’s office and he suggested that she should consider optometry. “I was in Dr. Ismail's office, the eye doctor I had had since childhood, and he suggested I consider optometry. We talked a bit, and when he mentioned binocular vision as a specialty I could consider, I was immediately interested.” It promised to bring together a number of Amanda’s goals and passions. After one of her brother’s surgeries, he exhibited an eye turn and she still remembered that desperate desire to heal him. And since seeing the jerseys decorating her ortho’s office, she was intrigued with the connection between medicine and sports and the importance of binocular vision.

Her future, until that point indistinct because of the abundance of opportunities, started to become clear.

A singular focus

With a sharpened vision and her characteristic motivation, Amanda was accepted at Nova Southeastern University and dove headlong into optometry school. In typical fashion, she excelled inside and out of the classroom. “I was president of our class every year except for the year that I was SGA president because you can't do both. I was the first optometry student to ever be overall NSU student of the year for the whole university, which is one of the awards I'm most proud of. I did it all because it was fulfilling to help my classmates and feel I was making a difference. I wanted to leave the program better than when I started.”

In a strange twist, her future again was murky because of too many opportunities as opposed to too few. Her plans to marry a man she had met at UCF—her fellow mascot—and move north to Orlando were thrown a curveball when she was given the chance to join the optometry practice that had been working with the Miami Dolphins for decades. For the cheerleader, the dancer, the barrel rider, the athlete, the mascot, and most of all the doctor, it was too big an opportunity to pass up. So, Amanda and her new husband settled in south Florida and the practice she calls home to this day.

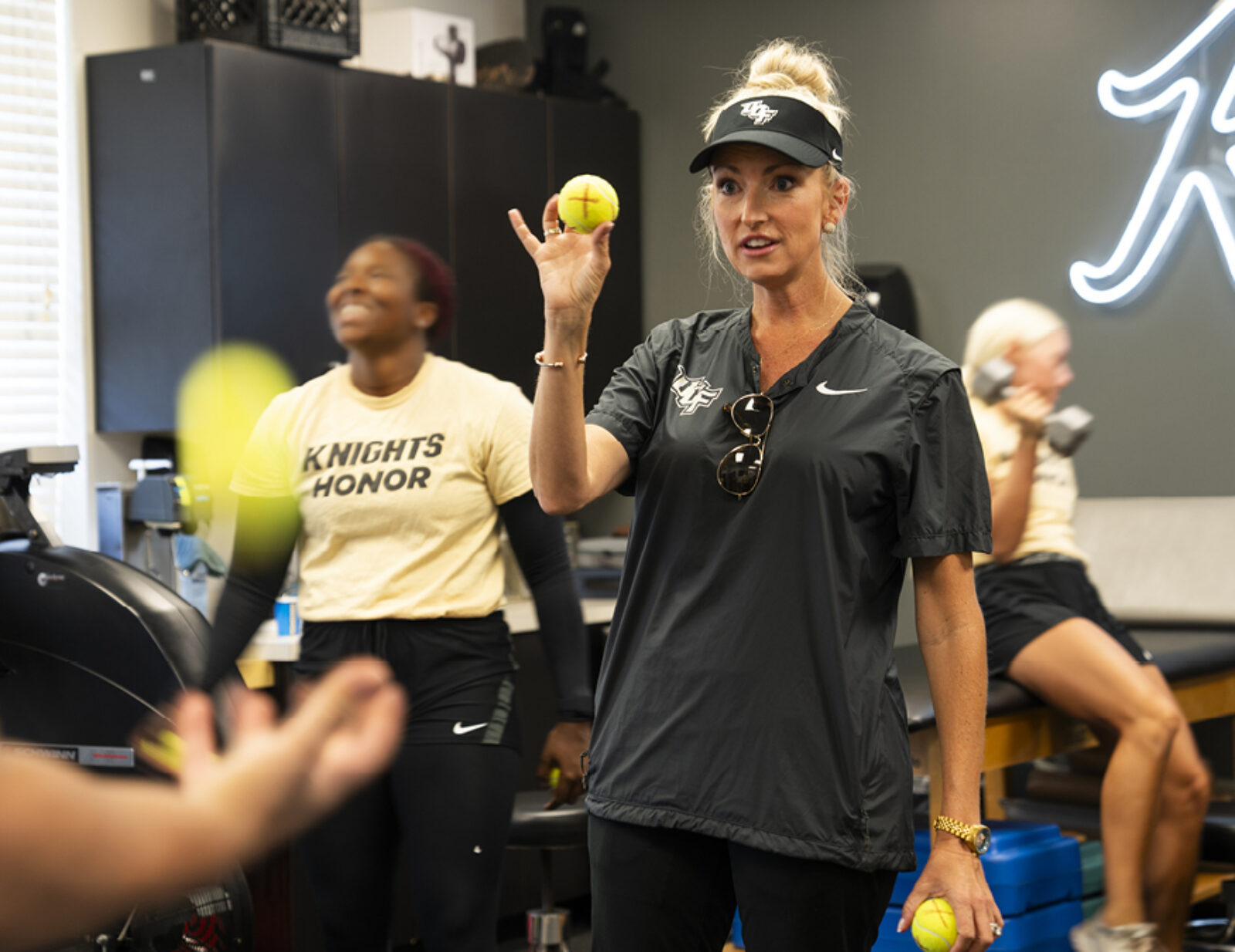

But instead of settling into a comfortable routine, things only got busier. She began, as the practice’s most junior doctor, seeing patients and doing occasional vision therapy for children. And slowly, over time, she started working more with the college and professional sports teams in Miami, Orlando, and beyond. It was the fulfillment of a goal that first took shape sitting in the orthopedist’s office and staring at the jerseys that decorated the walls.

“The first thing that I did was work with Nova Sports Medicine. I already had a connection with the baseball team because I had done vision training research with them as a student. I said, ‘So now that I'm actually a doctor, you guys don't have any type of routine evaluations to know what your athletes need and what they don't need.’ I think I brought them donuts and my laptop and I did a PowerPoint presentation in their training room. I didn't charge anybody. I just wanted to work with the team. Eventually I brought in optometry students so 200 athletes would get evaluated and 20 students would get experience.”

Her own increasing experience led to more work and tighter relationships with other teams including UCF, the Miami Dolphins, Miami Heat, InterMIami CF, and a number of others. “I still remember being at the Orlando Magic getting ready to see Dwight Howard when Coach Patrick Ewing walked in.” She was temporarily the little girl and the rabid sports fanatic again. “I’m a fan, but I need to remain calm and be the doctor. What's cool to me is when I know that I helped an athlete perform better by making a vision correction.”

Today, her many interests and frantic schedule often see her pause and ask herself some variation of "What’s today? Wednesday? No…Thursday.” And Thursday might mean a lecture, or an interview with Fortune magazine, running to a baseball practice, or a check in with UCF Football and the 30 athletes that are wearing a new sports performance contact lens that mitigates light and reduces glare.

"I called my mom and told her the whole story. I was a new doctor, so this was all new to me. And my mom said, ‘Amanda, your brother died 20 years ago today.’"

Not in time for Greg, but for Ashley

Of course, her impact on people’s lives extends beyond 7-foot centers and speedy wide receivers. Amanda had wanted to be a doctor since she saw her brother losing his battle to a brain tumor. At the time, she couldn’t help him, but time—and fate—are strange and powerful things.

"I was not practicing for very long, maybe a year or so, when a cheerleader came in after practice for a regular eye exam. She was probably 11 or 12. She was 20/20 and we were just doing routine testing and she was repeatedly getting peripheral testing wrong. I would hold up one finger and she would confidently say five. We ended up doing a full visual field test and I sent her off to have imaging, which revealed a brain tumor. They scheduled her for surgery two days later—very urgent. I called my mom and told her the whole story. I was a new doctor, so this was all new to me. And my mom said, ‘Amanda, your brother died 25 years ago today.’"

Heading in a new direction

Sports have undoubtedly changed in recent years, but in no way more than the way teams think of and handle concussions. In decades past, athletes were expected to “suck it up and get back out there.” But with medical advances around brain trauma and CTE, concussions became an issue that parents, athletes, and sports franchises finally began taking more seriously. Concussion protocols have changed and are now part of athletic safety and recovery. Unfortunately, discussions and examinations of vision after a head injury are not.

But Amanda is on a mission to change that.

Her passion around the subject was born in part from her own concussion. “I wish I had a cooler story, but actually I guess there's a little bit of interesting twist because I was speaking at the American Optometric Association on concussions in the NFL just a few days prior. I flew back into town and saw UCF football the next day and did their vision evaluations. And I had all the equipment in the back of the car, including an auto refractor that I had borrowed from the Washington Nationals. I was just sitting in the passenger seat half asleep, and we got rear ended at a light and my head went back and hit the A-frame. When I lecture about it, I always like to show the pictures of the accident, which wasn't so bad. I was more upset at the time that the auto-refractor could have been damaged. But even with a minor accident, you can still have really impactful things that happen. I had almost every visual symptom of a concussion possible within days. Patients like that need our help.”

She has become a leading advocate on the subject and is pushing for fundamental change in the way traumatic brain injuries are treated. Her advocacy has included speaking to Congress about the importance of eyecare in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients. “I'm really proud of going to Capitol Hill and speaking about how a high percentage of people with traumatic brain injuries are going to have visual symptoms and these are the things that pediatricians and primary care doctors should watch for. It can make a dramatic difference in the lives of these patients to get an appropriate referral to optometry.”

It’s an example of how the focus on sports vision is transforming lives well beyond the playing field and how a single optometrist can facilitate real change.

The right choices in the end

Days filled with helping children. “With young Ashley, at that point I was sure this is what I was supposed to do. That's why I went to optometry school. Ashley's going to grow up and live an amazing life and everything I do from here on out is just gravy."

Changing the conversation around concussions. “My goal is to move the needle and make optometry an integral part of every sports team. Every pro team, every college team, every high school team should have an eye doctor affiliated with them, not just because it improves performance, but because it improves safety and will likely reduce injuries. Parents and coaches and athletic trainers will understand the importance of eye care. And that's where I'm really trying to make a difference.”

Working closely with athletes to help them achieve their full potential. “It's definitely exciting when you can make a difference and you can see your athletes performing. Watching UCF this past year was very stressful for me. I'm just watching them, and thinking, ‘Don't drop a pass…don't drop a pass.’ And every time somebody scored a touchdown my kids would look at me. Many times, I was able to look back at them and say ‘Yeah, he's one of mine.’”

In the end, Amanda Nanasy, the girl with so many choices, made all the right ones to help so many others and to become everything she wanted to be.