Is it possible to dream about something you’ve never seen? Some would say yes…you can dream about a plant with butterflies for leaves, but most likely only after you’ve seen both plant and butterfly. Many would say no…that our dreams are manifestations of what we’ve seen and experienced in our waking lives.

If you hold with the second viewpoint, it makes sense that little Chaka Norwood never dreamed she could be an optometrist—because she had never seen one who looked like her.

Seeing inspiration everywhere

Mound Bayou, Mississippi isn’t like any other town. It was founded in 1887 by freed African-Americans from Davis Bend, a community started in the 1820s by Joseph Davis, brother of future Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Founded to be slightly more progressive for its era, it allowed self-leadership, provided better nutrition and healthcare, and encouraged enslaved residents to become small merchants. After the Civil War, Davis Bend became an autonomous, free community. But eventually, agricultural depression, falling cotton prices, Mississippi River flooding, and white hostility contributed to the failure of Davis Bend.

Isaiah T. Montgomery, a former resident of Davis Bend, founded Mound Bayou in the bottom land wilderness and, by 1900, two-thirds of its land owners were Black farmers. But as cotton prices fell again, the town suffered a severe economic decline in the 1920s and 1930s.

After a fire destroyed much of the business district, Mound Bayou began to revive in 1942 with the opening of the Taborian Hospital by the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor. For the next decades, the hospital provided low-cost healthcare to thousands of Blacks in the Mississippi Delta. The town thrived and attracted prominent and successful citizens to become residents.

“We have great people that come from Mound Bayou because we had teachers that cared about us and loved us. They taught our parents, and everybody knew everybody. If you got caught acting up, you heard, ‘I'm going to tell your mama. I'm going to tell your daddy.’ So, we had a good foundation; all of our kids graduated and went on to college, and we have a lot of doctors, lawyers, accountants, teachers, administrators. Everybody from Mound Bayou seems to do something with their life.”

But even with all that history and all the examples of excellence, a young Chaka had never dreamed she could be an optometrist. In fact, eye care was not a regular part of her childhood. As many in the industry know, a child can go to a doctor regularly and visit a dentist every year, but never see an optometrist.

Until one day when they can’t see the blackboard.

“I was ashamed to ask the teacher and embarrassed that the other kids would say, ‘Why does she need to go all the way up to the board to see?’ So sometimes I would just lay my head down in class and pretend I was sick because I couldn't see the board.”

Finally seeing the future

In fourth grade, Chaka began to struggle in school. Not because of effort and certainly not because of intelligence. Because of vision.

“I was ashamed to ask the teacher and embarrassed that the other kids would say, ‘Why does she need to go all the way up to the board to see?’ So sometimes I would just lay my head down in class and pretend I was sick because I couldn't see the board.”

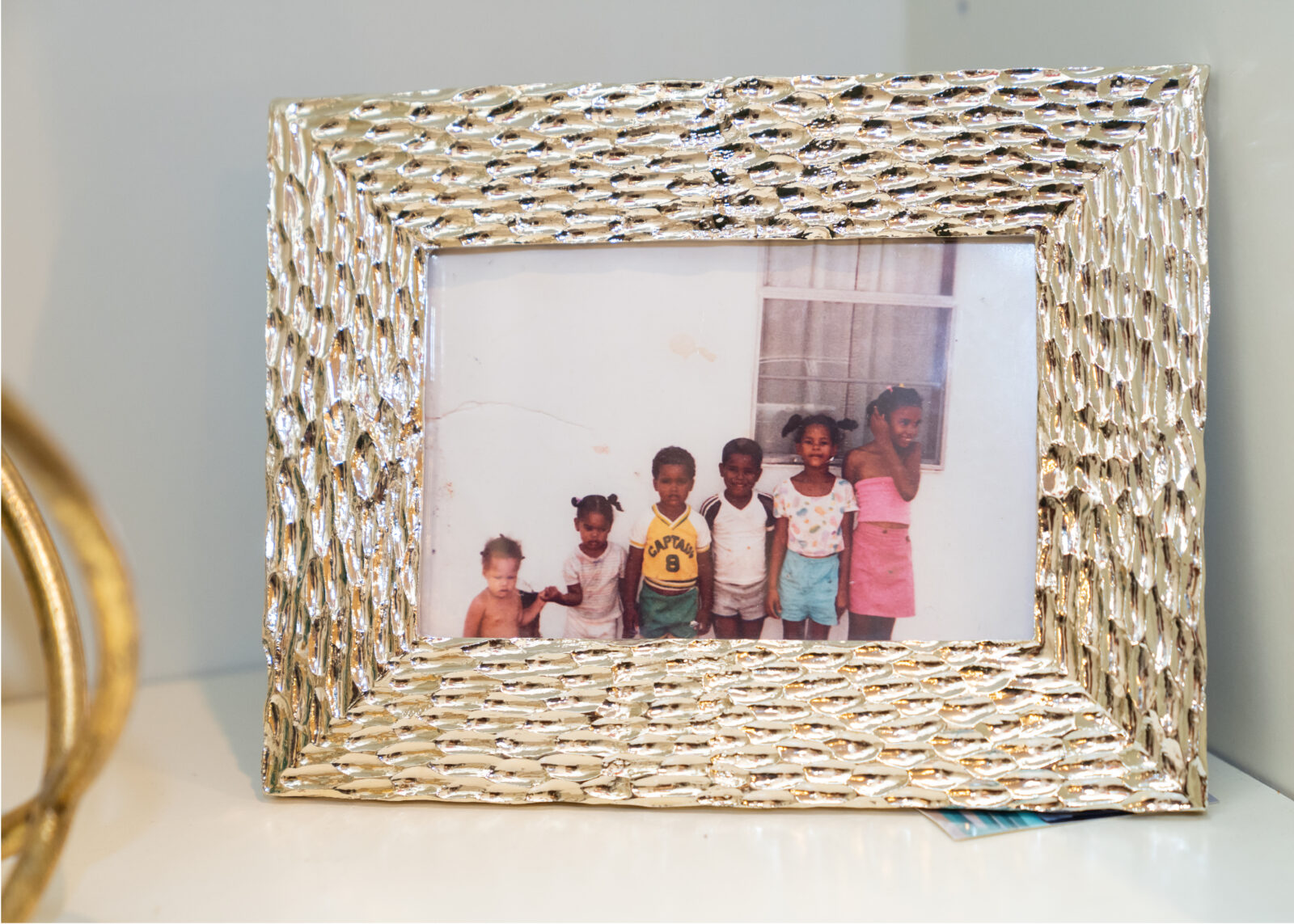

She told her parents about her struggles, but with six kids and not a lot of money, it was months before she saw an optometrist. She needed glasses. And she wanted glasses—a particular kind—very badly. For those not familiar with 1980s daytime television, Sally Jessy Raphael was a tabloid talk show host who served as a predecessor to other more famous names like Geraldo Rivera and Oprah Winfrey. Raphael’s signature? Prominent red eyeglasses. Chaka would sit and watch and think that someday she would get a pair of those cool red glasses. But she would have to wait for those.

She eventually did see an optometrist and get boring-colored glasses. When she did, everything changed. Chaka had always been a good and diligent student, but she was always asking a friend what was written on the board. Now, she thrived.

People around her began to ask what she wanted to be when she grew up. Sometimes she would say a lawyer, other times a teacher. She had role models for those and inspiration all around in Mound Bayou. “But I would just say something. I didn’t really feel those were right.” She had yet to see her future.

All that changed on a visit to an optometrist in Cleveland, Mississippi. He asked. She hesitated. He suggested optometry for the bright young girl without a clear direction. And a seed was planted.

I don’t see dead people

“We didn't really have counselors at the school to guide us in a career path. No one to say, ‘This is what you need to take in college to be an optometrist.’ So, I just started researching it on my own.”

Chaka enrolled at Jackson State University as a Biology major because the school did not have a pre-optometry track. In her junior year, she found out that Gross Anatomy was a required class in optometry school. At the time she thought, “That says I have to deal with cadavers. I don’t deal with dead people.” She immediately went to see her advisor and left as Jackson State’s newest Accounting major.

“I took one accounting class, I had no idea what that lady was talking about, and I quickly changed back to biology. I was like, ‘Well, I know I'm not going to optometry school, just let me just stick with this biology degree. But I don't know what I'm going to do because I can never work on a dead body, I could never do that.’"

Soon after that decision, a representative from the University of North Texas Health Science Center came to a career fair and talked to Chaka and three of her friends about obtaining a public health degree and working as a health administrator. When the college students without a lot of money heard the salary they could expect, the decision was made. “Okay, this is what we’re doing.” And off she went to Texas.

Chaka worked characteristically hard, graduated in a bit over a year, and started looking for a job. It didn’t go as planned or as promised. Instead of a health administrator, she took a job at a mental health agency auditing medical records. She found it less than rewarding and that brought a realization. "This is not what I went to school for. I still want to go to optometry school. That's what I had planned for since high school. I was going to be an optometrist.”

Chaka applied to the University of Houston and found that she was sharing the classroom with, yes, cadavers. After the long, strange journey to avoid them, she found that her fears were overblown. "This was not going to stop me, and when I took the course, I thought, ‘Oh, they're just lying there. It's not a big deal. It's not a problem. What are we going to eat for lunch?’ It’s funny, now but I rerouted my whole life just because of that one fear of a cadaver that couldn't do anything to me."

Seeing her way home

Throughout the odyssey that started when an eye doctor asked her if she would ever consider optometry as a career, Chaka never forgot what it was like to be that little girl needing glasses her family couldn’t afford. And she remembered the times when she lost or broke them and had to wait until her parents could afford to replace them. Upon graduation, she was in the position to make a difference. “I couldn’t see. Let me help other people see.”

And to Dr. Norwood, that meant helping the people back home. She set her sights on Memphis, where her family now lived. The journey that took her far away to Texas now reversed itself and a first job at a private practice in Jackson, Mississippi eventually led to an opportunity at a Sam’s Club in Jackson, Tennessee. It was closer, but still too far from the people who meant the most to her and an hour drive from her home. A four-year stint there ended when a Walmart only a few minutes’ drive from home had an opening for an optometrist. That lasted until 2018, when Dr. Norwood decided her dream could best be realized by opening her own practice.

“I just wanted to do more and have more equipment and take better care of my patients, so I thought, ‘Let me just start my own practice. And it’s going to be simple, simple, simple. Fill out the application, take it to the bank, I'm an optometrist, I've been doing this, I know what I'm doing, and they'll give me the money.’” Instead, the loan application was turned down by multiple banks. But just like the early residents of Mound Bayou found a sympathetic ear and supporters at their own locally owned bank, Dr. Norwood found the same at her small local bank. It approved her loan, and her own practice was within reach.

Enter Covid-19. Her first instinct was that it would be impossible to open a new practice during the pandemic. But Dr. Norwood saw other practices staying open and some getting even busier during Covid, so she decided to move forward. That bank had other ideas.

In the time that had elapsed in the early months of the pandemic, the bank required Dr. Norwood to re-apply. She found that she was still approved, but for significantly less than earlier in the year. It was an obstacle, but not an insurmountable one. Instead of buying equipment, she leased it at a considerable cost savings.

An unprecedented virus. A substantially reduced bank loan. A nightmare with her building contractor. Nothing could stop Norwood Family Eye Care from becoming a reality.

From inspired to inspiration

As a little girl in Mound Bayou, Dr. Norwood was inspired by the prosperous Black professionals all around her. It was a successful, thriving area turning out people who were the same. But in the years since, the area had experienced harder times and the children of the Bolivar County school districts needed more funding for programs and more adult role models. In their own way, Dr. Norwood and a few friends decided to do something about both.

“A friend from high school is a nurse practitioner and has a medical facility down in the Delta. She was in talks with the superintendent of the school district where we grew up and pitched the idea of school-based clinics." The team approach would provide needed healthcare services to the children and Dr. Norwood would do eye exams. Another practitioner would provide dental services; another would provide counseling. “She presented it to me, and I thought it was the coolest idea.”

From her base in Memphis, Dr. Norwood would make the drive to northern Mississippi on a regular basis. “I was seeing about 300 kids throughout a couple of districts, and we were able to get a lot of kids glasses. I know what it's like to be in a classroom and not be able to see. In many cases, parents probably can't take off work to take their kids to the eye doctor. So, it's nice when I can help them knowing that I was in the same school and the same situation.”

Dr. Norwood is living proof of the impact a pair of glasses can make to young students. But in a very profound way, it’s more than their need to see. It’s their need to see someone like themselves who has achieved success through hard work and perseverance. “I guess I’m a positive role model for them because they need to see a Black eye doctor. They say, ‘You're an eye doctor? You grew up here? You do this? You lived here? Okay, if she can do it, I can do it, too.’”

Helping others soar

Dr. Norwood’s service isn’t focused exclusively on school children. She remembers what it was like to be a little girl who couldn’t afford glasses, but she also was a college student needing guidance, and a young OD looking for mentorship. With a keen understanding that when much is given, much is required, Dr. Norwood devotes time outside the office to helping others—some on the same path as her, some on a very different one.

She currently serves as the optometrist for the Marshall County Correctional Facility, where she provides eye care services to people who have not had the same opportunity or outcome she did. Dr. Norwood also is a member of Black EyeCare Perspective, an organization dedicated to creating a pipeline for Black students into optometry, and takes a leadership role in reaching students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities with a goal of increasing the number of Black students matriculating through optometry school.

“I've spoken to students at several events at Southern College of Optometry and also told Black EyeCare Perspective that I wanted to be a mentor. Dr. (Janette Dumas) Pepper at SCO told me, ‘When you come and talk to these students, you're so real. You're so down to earth and you don't sugarcoat anything.’ My journey has not been an easy one, so I don't tell them it's easy. I tell them I got to optometry school and failed a class my first semester, so I had to repeat it. But look at me… I still opened my practice. I still did this.”

Dr. Norwood is also a member of the Ebony Eagles, a group of African-American optometrists in private practice who meet, exchange information about best practices, offer encouragement, and encourage each other to take leadership positions in reaching back to help other African-American students. “I hosted the Ebony Eagles meeting at my office a couple weeks ago, and the doctors in attendance signed up with Black EyeCare Perspective to be mentors.”

At times however, Dr. Norwood is looking for guidance instead of offering it. In those instances, she often turns to IDOC.

“When I was going through the process of opening and didn't know what to do or where to go, IDOC’s diverse resources guided me with advice about using a limited number of vendors, HR assistance, helping me get a handbook together…. The answers, depth, and detail I get from them is very different than what I get from another eye doctor who’s just my friend. Just being able to call and ask, ‘What should I do?’ They really helped me start my practice.”

And they also helped her achieve her dream that started as a little girl in front of daytime TV and took shape through a long and interesting journey. Recently, Dr. Norwood tweeted, “Hey, this was once a little girl who could not see, wanted her red glasses, and had to struggle and fight for those glasses. Now I have my own practice.”

Yes, Chaka Norwood has her red glasses. Gucci.

If you haven't watched Dr. Norwood's story, be sure to click here: